:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/steinbeck-56a48caf3df78cf77282ef2a.jpg)

For a while now, John Steinbeck has been a household name for most high school students. When we hear his name we think legendary writer, or Nobel Peace Prize recipient, or causer of late-night break downs of students (me right now). However you want to classify him, Steinbeck’s influence has undoubtedly permeated the world, not just in literature but in society as well. For that, Steinbeck also holds the title: Feminist Icon.

I’m being totally serious. John Steinbeck is a literal Feminist Icon. After reading his beautifully written short story, “The Chrysanthemums,” I wouldn’t be surprised if you told me that while Steinbeck was alive and writing literature, he also was leading a secret revolution against the patriarchy.

“The Chrysanthemums” is a story of defeat. The protagonist, Elisa Allen is a married woman but has no children. She lives in an isolated world dominated by men but finds strength when she tends to her chrysanthemums. Through a series of interactions with her good-intentioned yet emotionally-detached husband and a greasy, free-roaming tinker she randomly encounters, Elisa is ultimately faced with the truth she had always known. She has no voice in this world.

Some heavy stuff, right? The message Steinbeck conveys is heartbreaking but undeniable for the misogynistic culture of the time period, which many argue is still prevalent today. I found that Steinbeck’s importance in setting and use of symbolism to be most compelling and effective in revealing his truth.

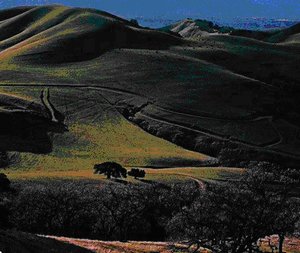

Let’s talk setting. The story takes place in Salinas Valley, California, a rural farmland.

Sound familiar? That’s because most of Steinbeck’s standout works like East of Eden, The Grapes of Wrath, and Of Mice and Men also take place in this isolated, picturesque nook in California. In fact, Steinbeck actually grew up in that same valley – his childhood home still stands, now serving as a restaurant for Steinbeck-aficionados.

Writing during an era where the Depression loomed and passed, Steinbeck found his passion in telling the untold stories of the American dream. Stories of misfortune, fate, and injustice. Salinas Valley is so isolated from the rest of the bustling state of California and the rest of society, those who reside there are often forgotten or looked over.

The story of Elisa begins in her quaint yet separated farmhouse in the valleys. More specifically, for the majority of the plot, the reader only ever sees her within the perimeters of fencing that surrounds her house. She spends most of her time gardening in her front yard, nurturing chrysanthemums, barely skimming the barrier that separates her from the rest of the world. Elisa’s husband, Henry, tends to the land outside of their house. He has the freedom to roam the Earth, the acres and acres of the farm they have. There is one scene where Elisa “saw [Henry and Scotty] ride up the pale yellow hillside in search of the steers.”

Later on, Elisa encounters a strange tinker, who travels from Seattle to San Diego and back, doing business with whoever he meets. He packs his life into his wagon and just follows where the road leads him. This man serves as another reminder that Elisa will never have freedom. When she expresses her admiration of such an adventure, the tinker quickly brushes her off saying “It ain’t the right kind of a life for a woman.”

Here Steinbeck highlights the oppression that women face. Henry, the husband, is a surface-leveled man who works all the time, Scotty (mentioned above) is just an irrelevant helper, and the tinker is uneducated and disheveled with no purpose, yet for some reason, they all deserve the right to freedom except Elisa? Sounds pretty bogus to me. Elisa is a strong, smart woman in her world (I’ll get to that later) who just wants to be shown appreciation and affection. According to Stanley Renner in his review, The Real Woman Inside the Fence in “The Chrysanthemums,” Elisa is a “… strong, capable woman kept from personal, social, and sexual fulfillment by the prevailing conception of a woman’s role in a world dominated by men…”

Now, the symbols. The most obvious symbol of the story is revealed right in the title, chrysanthemums. The Chrysanthemum flower is one that you can’t miss. It consists of layers of a multitude of intricate petals, usually adorning in a vibrant color like yellow or bring magenta. We don’t know much about Elisa as a person, but we do know that her chrysanthemums are her pride and joy. She knows every hack there is in order to take the best care of your chrysanthemums, evident in when she is giving some chrysanthemum buds to the tinker. When she tends to her chrysanthemums, she feels power and purpose.

Upon analyzing the short story, I would like to argue that Elisa’s chrysanthemums symbolize Elisa herself and her true potential. Alone in her own world, she is the only one who knows what she wants. I mean, her husband certainly doesn’t. In taking care of her chrysanthemums, she is taking care of herself, growing stronger and stronger every day. There is a moment where a surge of life runs through her as she carefully trims the flower. “Her face was eager and mature and handsome; even her work with the scissors was over-eager, over-powerful. The chrysanthemum stems seemed too small and easy for her energy.” The complex structure of the Chrysanthemum represents the inner-workings of Elisa. It symbolizes that, contrary to what men thought at the time, women are actually intelligent with multi-dimensional minds.

Yet, Elisa and her chrysanthemums are also one and the same, in the sense that they are both trapped. The chrysanthemums have their place in a “…little square sandy bed…” inside a garden that is surrounded by fences. Just like her tragic flowers, Elisa also seems to live her life in a cage. Whether her house is the cage or the world is her cage, she can never break free of the gender roles that chain her.

Yet, Elisa and her chrysanthemums are also one and the same, in the sense that they are both trapped. The chrysanthemums have their place in a “…little square sandy bed…” inside a garden that is surrounded by fences. Just like her tragic flowers, Elisa also seems to live her life in a cage. Whether her house is the cage or the world is her cage, she can never break free of the gender roles that chain her.

Later in the narrative when Elisa encounters the tinker, in a way, she is swept off her feet. As soon as he displays interest in her flowers, she swoons and right away shares her knowledge on how to care for them. In the tinker caring about the chrysanthemums, Elisa feels as though he cares about her too as a person. Although Henry is a decent man and husband, he never shows affection or cares for Elisa. Deprived of this intimacy, Elisa right away is enamored by the tinker. In the end, Elisa gives the chrysanthemum buds to the tinker, putting her trust in him, as if giving him a piece of her heart as well.

I won’t give the ending away but let’s just say that the tinker did NOT deserve her chrysanthemums. In “Ms. Elisa Allen and Steinbeck’s ‘The Chrysanthemum'” Charles Sweets concludes, “[Eliza] has allowed herself to become emotional, ‘the trait women possess,’ whereas men conduct business unemotionally.”

This was a woman’s life. I feel pure anger thinking about what it must’ve been like to walk the shoes of a woman in the 1930s, being restricted on where I could and could not be. I mean, come on, women were just given the right to vote 17 years prior to when “The Chrysanthemums” was published. People need to read this book. And when they are done reading it, they need to be outraged. While obviously, sexism isn’t as outwardly direct today as it was 80 years ago, but it is still prevalent. All I have to do is hop on Instagram, do some searching, and soon I will find a pool of misogynistic comments.

“The Chrysanthemums” is a simple yet impactful story. It is an enjoyable read because of its glimmering imagery and effortless plot. However, it stirred something inside of me. And as I finished the last line of the last page, I felt the power of centuries worth of women, like Elisa, speaking their truth. Breaking free from the roots that kept their mouth shut.

Great job, Steinbeck. Very modern.

–

Works Cited

Renner, Stanley. “The Real Woman Inside The Fence In ‘The Chrysanthemums.'”Modern FictionStudies 31 (1985): 305-17.

Steinbeck, John. “The Chrysanthemums.” Literature and the Writing Process. Ed. Elizabeth McMahan, Susan Day, and Robert Funk. 2nd ed. New York: Macmillan, 1989. 330-6.

Sweet, Charles A., Jr. “Ms. Elisa Allen and Steinbeck’s ‘The Chrysanthemums.'” Modern Fiction Studies 20 (1974): 210-14.

I love your interpretation of “The Chrysanthemums”! Even though I’ve never read this story, I just might for this Friday’s post. I think the chrysanthemums symbol that you discuss is really interesting in characterizing Elisa. How you describe both Elisa and the chrysanthemums to represent being trapped in one way or another (literally and figuratively) is a really compelling way of describing the position of women back in the 1930s. Also, I’m interested in what the tinker did that made you say he did not deserve Elisa’s chrysanthemums. I’ve only read Of Mice and Men by Steinbeck and given that Steinbeck was a male in the 1930s, I’m intrigued by his take on feminism and how woke he is with this story. Honestly, good for him for being a feminist when no one else was back then and good for you for shouting him out on that!

Thanks, Kelly! You should definitely give this story a read because there is so much more to it that I didn’t get to cover in this blog. I’ve also read East of Eden by Steinbeck and while the stories have two completely different plots, I can definitely detect his distinct voice in both.

The feminist aspect of Steinbeck came as a very pleasant surprise!

Jessica! I really, really hear your voice coming through and I’m right with you about being angered at women’s treatment in the early 1900s. I was actually really surprised to hear that Steinbeck’s a feminist icon because, for all of high school, I’ve always just grouped him with every other male author we’ve had to read. I think the dread of reading another high school novel for yet another English class has made me blind to the stories behind the authors.

From your summary of the short story, especially that cliffhanger you left me with, I really want to read it now. Although we talked about not identifying with characters in the beginning of this year, I think I’d very much like to defy that and connect with Elisa. I think Steinbeck would, arguably, very much like that, too, as a feminist icon!

I can totally relate to being blind to the stories behind the authors of the novels we read, which is something I feel bad about now, however, I think it’s understandable! You should definitely read this short story because there are so many aspects of the it that I didn’t get to mention in my blog that makes this story so iconic. If you do read this story and connect with Elisa, prepare to have a very heavy feeling in your heart after you’re done!