If you’ve ever been to the Field Museum, you’ve probably seen glass cases containing all sorts of rocks and minerals. If you were like me and didn’t know a single thing about them, you probably didn’t find them to be too interesting. But as I learned more, I was able to identify different types of rocks and minerals, and found a special type of fascination in my hobby. So today, I will be sharing a little bit about these wonderful earth materials.

If you’ve ever been to the Field Museum, you’ve probably seen glass cases containing all sorts of rocks and minerals. If you were like me and didn’t know a single thing about them, you probably didn’t find them to be too interesting. But as I learned more, I was able to identify different types of rocks and minerals, and found a special type of fascination in my hobby. So today, I will be sharing a little bit about these wonderful earth materials.

First of all – what is a mineral? The proper scientific definition includes 4 qualifications: a mineral must be a natural occuring, inorganic compound with a well-definite chemical composition and orderly internal structure. Essentially, this means that a mineral must be naturally found in the ground – it cannot be made in a laboratory or elsewhere. A mineral must also be solid at room temperature; as a result, ice can be considered a mineral, while liquid water and water vapor are not. And lastly, it must have a defined chemical composition. Scientists from all across the world need to look at the chemical formula and say, “Yes, I agree that it’s quartz.”

Scientists have identified over 4,000 different species of minerals. Of course, I can’t talk about every single one, so I will be highlighting some especially interesting minerals and their special properties. Trust me, this will be much more interesting than you think.

Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth’s continental crust, accounting for 20% by mass. It has a chemical composition of silicon dioxide(SiO2) and is a critical rock-forming mineral. Oftentimes, it appears as a clear to white crystalline structure, although impurities can create many shades of color. For instance, amethyst is a type of quartz that includes iron impurities, which gives it a characteristic violet color. Other variations of quartz include rose quartz, smoky quartz, and agate. Quartz is often found in felsic (i.e. lighter colored) rocks such as granite and rhyolite, as well as some sedimentary and metamorphic rocks.

Olivine is another very significant mineral, a primary constituent of mafic (darker colored) rocks like basalt and gabbro. It’s also a silicate mineral, meaning that it contains silicon dioxide, but olivine also has compositions including a large quantity of magnesium and iron. Olivine is characterized by its green color, and it’s a primary component of Earth’s mantle (the layer underneath the crust).

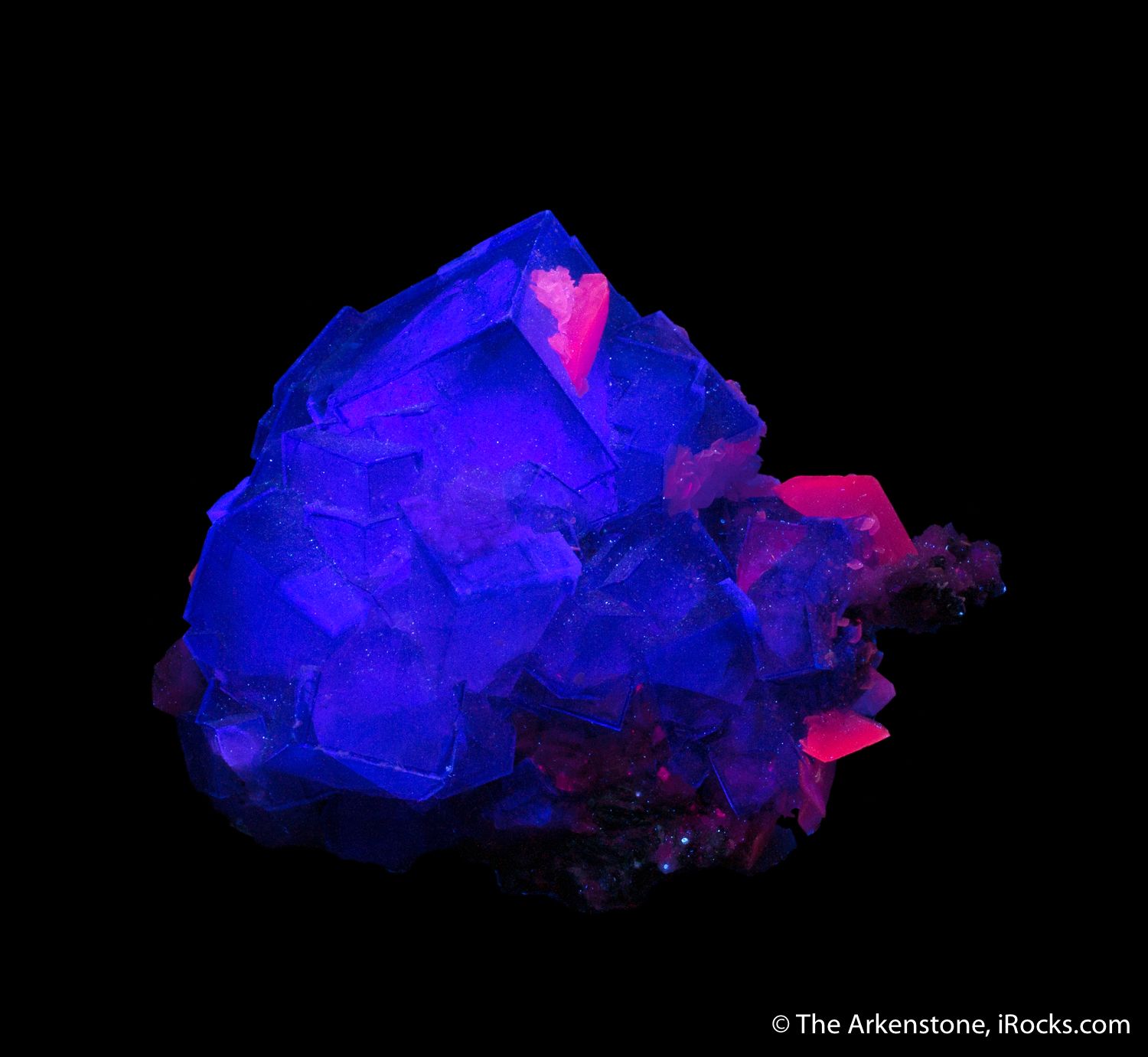

One of my personal favorites is the mineral fluorite. Fun fact – it’s also the Illinois state mineral! Illinois is the biggest producer of fluorite, which has a chemical composition of calcium difluoride (CaF2). It varies in all sorts of colors, from green to purple, blue, and orange. Another interesting property of fluorite is its fluorescence for which it is named. Under an ultraviolet light, the mineral will emit a bright blue color.

Another unusual and interesting property that some minerals possess is radioactivity. The mineral uraninite, also known as pitchblende, is the main ore of uranium and extremely radioactive. Its chemical formula is uranium dioxide, or UO2, and it usually appears as an unassuming black mineral.

Minerals also come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Stibnite, the ore of the element antimony, has an extremely unique crystal habit (the shape that a species of mineral tends to form). It’s blue to gray in color, and takes the shape of long, jagged rods known as a bladed crystal habit.

You can’t talk about minerals without also talking about diamond. Diamond is formed from pure carbon, compressed at high temperatures and pressures to create the brilliant mineral that we know. Similar to quartz, elemental impurities can create different colors, such as blue, brown, pink, orange and red. Diamond is also the world’s hardest mineral, earning a rating of 10 on the Mohs Hardness Scale.

Did you know that sapphires and rubies are actually the same mineral? When corundum contains traces of the element chromium, it forms the red color of ruby, and titanium creates the sparkling blue of sapphire. Corundum is also a very durable mineral, with a hardness of 9 on the Mohs Scale.

There are also some minerals used for very practical purposes. Halite, or more commonly called rock salt, is the mineral form of sodium chloride, which we use every day in our food. Another example is gypsum, which is widely used as plaster and drywall.

There’s an insane amount of minerals on this planet, and I doubt that anyone knows them all. But many of them play important roles in Earth’s geology and our lives, whether it is forming the rocks that build mountains or using them to salt our food. In the end, we can’t live without them.

Interesting, Dingjia! I don’t remember the last time I thought about minerals and the role they play in our world. I definitely learned some interesting facts from your blog.

First, I didn’t know quartz accounts for 20% of the mass of Earth’s continental crust! That’s a huge chunk! I also recognized the chemical formula SiO2 that we learned in AP Chemistry, which is used to form network solids. Silicon dioxide is harder than steel, so I thought that was a cool fact.

Another cool thing I didn’t know about minerals is that fluorite is Illinois’ state mineral! I didn’t even know state minerals were a thing, haha! I’m surprised fluorite can come in purple and orange. I thought they were usually just green or blue.

Lastly, I didn’t know that sapphires and rubies actually come from the same mineral! This puts an interesting twist on Pokémon’s Ruby and Sapphire versions. I also didn’t think corundum had a hardness of 9 on the Mohs scale. That’s one off from how hard diamond is! No wonder why rubies and sapphires are praised so highly.

Minerals are quite fascinating—they are the little building blocks that form our world… that being said, your blog reminded me how little I know about them! Thanks for sharing this cool information.

Hey Dingjia,

It was great reading your blog! I definitely learned a few things about minerals. I was surprised that there are over four thousand types of minerals! That’s an unfathomably large variety of them, considering there are only about one hundred elements on the periodic table that can be found naturally.

I didn’t know that quartz was actually so abundant in earth. You mentioned that it is the second most abundant mineral, which makes me think whta thte most abundant mineral on earth is. I also noticed that the formula is generally SiO2, which I also recall to be sand. Is sand a form of quartz?

I also see that these minerals all have super special properties, whether that is their exotic colors, their fluorescing properties, or their hardnesses. I see that diamond is rated as one of the hardest minerals on earth! I know that it has a bunch of industrial applications, but since it is so rare, how do we get enough of it to use it on an industry scale?

I did some research on the problem above and found that we do indeed synthesize diamonds in labs (some fancy “diamond growing” technique), but I was curious, since these diamonds are synthesized instead of naturally made, are they still considered minerals?

Just a few questions I had. Once again, I loved reading your blog!

Andy T

Hey Andy,

Great questions! I’m glad you thought my blog was interesting.

The most abundant mineral in Earth’s crust is actually feldspar, and it accounts for roughly 60% of the crust by composition. Feldspar is actually a family of minerals that are all aluminosilicates (containing aluminum and silica). The family can be broken down depending on which cations it includes, usually sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. For instance, albite – another mineral – is a sodium feldspar, with formula NaAlSi3O8. If you want to learn more about feldspars, I recommend reading the Wikipedia article.

Sand is interesting. It’s not actually classified as a mineral, because there can be many different chemical compositions that still form sand. But the short answer to your question: yes/sometimes.

First off, sand, or any other granular materials like silt, clay, or gravel, are formed by the weathering and erosion of rocks to form sediments. It’s very common for this process to occur by water and wind, which is why we see beaches near the coast and sand dunes in the desert.

These granular materials are determined by grain size – if a soil particle is within the range of 0.06 mm – 2.0 mm, then it’s classified as sand. In contrast, a particle like gravel will have a grain size of 2.0 mm – 64 mm (purely by scientific definition).

Now, about the chemical composition: it depends on the type of rock that is eroded. If it’s a rock like granite (which is most common), the sand will most likely be silica (SiO2, quartz), as you mentioned. But it’s also possible to have sand composed of other molecules like calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Coral reefs are often composed of minerals containing this molecule, so you will often see calcium carbonate sand on tropical beaches, such as in the Carribeans.

About lab-grown diamonds: no, they’re not minerals, since they don’t fulfill all the requirements. But that doesn’t mean they’re useless – we can still use them for all the things naturally-formed diamonds are used for.

Hey Dingjia, before I read your blog post, I like to look at the title and comment on it a little bit, so I just wanted to say that the title is really nice and it seems very professional and put together from a first glance at the title and your blog. After reading through your blog, I want to say that I really liked how informative and helpful this article is. I really liked the way you explained what a mineral is and the ways to identify and name a mineral and the ways you incorporated a multitude of various minerals into your paper with pictures and explanations of their relevancy in society today. Overall, you did a very good job of explaining the minerals in a way that makes them entertaining to learn about and at the same time does a really great job of informing the audience about the many minerals you have in your blog. You were 100% right when you said this wasn’t just a boring blog about rocks and overall, I really enjoyed reading your blog and learning about those minerals that you covered.

Excellent post, Dinjia!

Hey Dingjia! Nice post. I’ve always thought of minerals as some of the coolest things that the earth produces. Something about the immense variety of color, shape, and texture of… rocks is just too surreal. That being said, I am nowhere near well versed in anything mineral related, I just like looking at em. Your explanation on the definition of a mineral was very clear and I was shocked to hear that ice could be considered a mineral which I found interesting since ice generally is in a perpetual state of melting at room temperature, so I would have thought that it could not count as a mineral because of the requirement that a mineral must be solid. My favorite of the minerals you depicted (thanks for putting up some pictures, by the way, I spent a a good deal of time admiring each one) is probably stibnite, which I didn’t even know existed until now. I love the shade of blue of the stibnite, especially when paired with the shine of its crystalline structure, it looks almost alien. The blades extending out of the crystal are super eye-catching. Fluorite has also consistently been one of my favorites due to the incredible variety and combinations of color that it can have, along with the fact that it strangely emits a blue light when shined with UV light as you mentioned.