Disclaimer: Take this information with a grain of salt. I’ve written this blog not only to share this information with y’all but also to test my understanding of some recent research I’ve undertaken to grow my knowledge base in the weight/powerlifting world and increase the efficiency of my training. I am in no way qualified to coach this sport; I’m just a rookie who wants to do things right.

I also would like to clarify that though I may have built a slight reputation as a calisthenics athlete through my various interactions with Alex Jang, I’ve poured much more time in my latest 2-year fitness period into general bodybuilding exercises and powerlifting movements. I’ve just recently taken on the research of various training techniques because the renowned weightlifting youtuber Clarence Kenendy has piqued my interest in the two Olympic movements: the snatch and the clean and jerk. Though I’m currently in the drilling phase to perfect my technique regarding these two movements, I would soon like to adopt a structured training regimen for each of my compound exercises.

The Basics

Training can be divided into macrocycles, which are made up of mesocycles, which are made up of microcycles, as depicted by the diagram above. A basic macrocycle like the one in the picture can be made up of 13 weeks, split into 3 mesocycles. The first two mesocycles are each 4 weeks long, and the last one is 5 weeks long. Each of these weeks can represent a microcycle. By the end of this blog post, our goal is to be able to create a simplified microcycle by defining the reps, sets, and intensity of the weights you will be moving each week in order to successfully implement progressive overload and increase your one-rep max (1RM).

Relative Intensity

Before we begin structuring a basic program example, we need to define relative intensity, an important concept that we’ll center our example around.

![]()

While absolute intensity is defined simply as a percentage of your 1RM, relative intensity takes into account the number of reps you perform per set, along with the amount of weight you move to gauge how the entire set will physically feel to the lifter relative to their 1RM. The above rep max chart displays how many reps you can expect to perform with a certain percentage of your 1RM weight on the bar (AKA your projected rep max for that intensity). With that in mind, the formula to calculate your relative intensity is your absolute intensity divided by your projected rep max.

Relative Intensity = Absolute Intensity / Projected Rep Max

For example, if you plan to begin training sets of 6 reps with 70% of your max on the bar,

Relative Intensity = 70% / 85% ≈ 82.4%

This means that you will begin your training at a relative intensity of 82.4%. So why is number important? Most beginners would make the mistake of overlooking this calculation and choosing a linear progression with respect to their 1RM. Let’s say they begin training with 6 rep sets at 70%, and then move on to 6 reps at 75% the following week. Throughout this week, they’ll be training at a relative intensity of ~88.2%, so as expected they’ve actually bumped up their relative intensity. Feeling good on the third week, they may decide to move up in weight once more to 80% of their 1RM. Naturally, as a lifter approaches their maximum load, they drop the number of reps they perform per set. So for the third week, this imaginary lifter will decide to perform 4 reps per set at 80%. If we calculate their relative intensity now, it will be ~88.9%, just barely above last week’s.

The problem here is that our lifter has just made a huge jump of 5.8% in relative intensity between the first and second weeks, but just a tiny step of 0.7% between the second and third weeks of training. Statistically, most athletes agree that relative intensity should increase linearly by 5% or less each week.

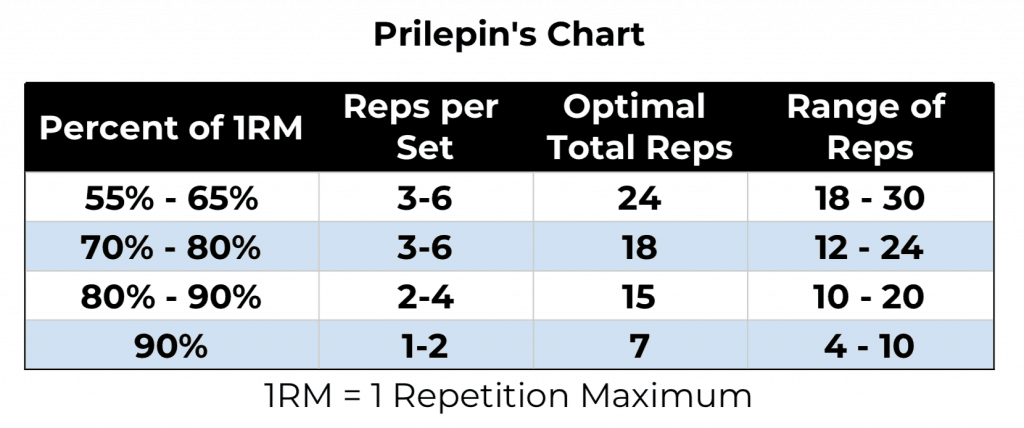

Prilepin’s Chart

Your individual training sessions for a movement will be composed of warm up sets and working sets. Throughout your warm up sets, you’ll be working up from light weights, generally starting with just the 45 lb bar, then adding weights until you reach your working set intensity. It is generally recommended for athletes to begin training their working sets with at least 70% of their 1RM on the bar, but how can they figure out how many working sets and reps to do?

Here’s where Prilepin’s Chart comes in. Devised by A. S. Prilepin through numerous years of observing Soviet Olympic weightlifters, Prilepin’s Chart acts as guidelines to decide how many sets and reps you should do at a given absolute intensity. For example, if for the first week you want to work with 70% of your 1RM, we can observe the second row of Prilepin’s Chart. 70% is on the lower end of the 70%-80% range, which means in the last column we want to work with the maximum range of reps: 24. Thus, you should perform 6 reps per set, giving you a total of 4 sets. Conversely, if you were working with 80% of your 1RM, you would want to perform a total of 12 reps, so you would do 4 sets of 3 reps at 80%.

And there you have it, the basics of programming for lifting. These guidelines were originally intended for Olympic lift training (the snatch and the clean and jerk), but over the years they’ve carried over to powerlifting movements as well (bench, squat, deadlift). I’d say for any heavy compound movement utilizing a barbell, you can use these guidelines to work both smarter and harder.