If you had asked me four years ago, “Do you enjoy writing?”, my answer would have been a resolute “No”. No explanation, no elaboration, nothing. To be honest, I never felt like it was worth my own time (or anyone else’s, for that matter) to listen to what I had to say about writing—a subject which, let’s just say I’ve not had quite the “affinity” for. Was my answer perhaps, at least partially, based on such a sentiment being shared among my peers? Maybe. Was my lack of “affinity” towards writing all of my own doing? Very likely, too. Even writing this, my brain from just a year ago would have uttered the same feelings: “You don’t like writing, so stop thinking about it this much”.

But in the eight years in which such an affinity has evaded me, my thoughts towards not thinking about writing, as it turns out (unsurprisingly), led me to think about writing all-the-more often. One thing led to another, and here I am, writing a final blog post for AP Literature—and I am enjoying myself? If blogging as a part of this course has taught me anything, it’s that with a little bit of creative input, you truly can find enjoyment in anything. In previous English classes, I never enjoyed the freedom which blog-writing has granted me this semester; even days where we could “write creatively” never felt as such. Yet here I am, given true, boundless freedom of creativity, enjoying the writing process more than I ever have before.

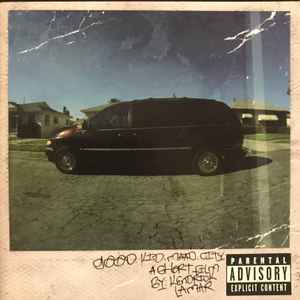

One blog which stands out as particularly fulfilling was my “artist review” of sorts, where I ranked the discography of Kendrick Lamar, a generational talent in the hip-hop scene—a topic which, especially in the realm of academics, I don’t get the chance to discuss. Having the creative freedom to talk about such a topic, about such a passionate subject, fueled my love for the subject even more. My blogs felt like my own little world, with each reader, or visitor, fueling my enjoyment for building upon such a world.

Apart from the frequent writing in the form of blog posts, I found myself similarly developing a newfound enjoyment for reading, too, a commonplace throughout the entirety of this semester. Specifically, the novel I chose for the Voices Project, The White Tiger, felt like a breath of fresh air in the world of reading—just as I, through my blog posts, created a world unique to me, it was refreshing to see a unique voice, presented through the lens of a unique topic, in the world of literature. Though I highly recommend and adore The White Tiger, I have to be honest: the first fifty pages are a struggle, fortunately redeeming themselves by paving the way for an otherwise brilliant and eye-opening novel surrounding the Indian experience. Even though I, like the author and the main character, am of Indian heritage, I always found myself learning—a crucial takeaway from this project, and indicative of the influence under-represented voices hold in the formation of our own values, ideals, and worldviews.

So, as I wrap up my final blog of AP Literature, of high school, and perhaps of my life, what I’ve learned throughout my high school journey is this—don’t leave high school longing for more: longing for more friends, for a club you wish you would’ve joined, for an event you wish you’d attended. You only get high school once, so, especially for seniors, live it like that one Snickers commercial: like you’ve got “no regerts”.

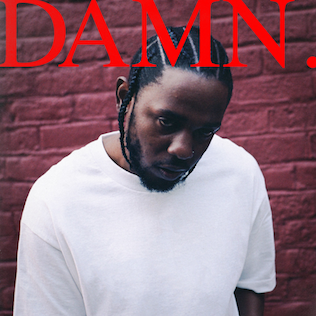

would consider the height of Kendrick’s commercial success, the less-focused but generation-blending DAMN. features many of his greatest rapping cuts, with DNA in particular being a personal favorite off of the project. In many ways, the commercial success of the album can be attributed to its mainstream appeal, with more modern rap cuts and even hints of pop appeal, as seen in LOYALTY featuring Rihanna. One aspect of the album which especially appeals to me is the often darker, angrier nature in his delivery on a large handful of tracks, almost suggestive of the album title, “DAMN.”, as being rooted in frustration and distaste with those who surround him in the industry. For newer Kendrick listeners, too, I believe that this is the best album to begin with when taking a delve into his catalog, as it masterfully blends both accessibility on the production and lyrical ends while still being a concept album with diverse storytelling tracks such as FEAR and DUCKWORTH.

would consider the height of Kendrick’s commercial success, the less-focused but generation-blending DAMN. features many of his greatest rapping cuts, with DNA in particular being a personal favorite off of the project. In many ways, the commercial success of the album can be attributed to its mainstream appeal, with more modern rap cuts and even hints of pop appeal, as seen in LOYALTY featuring Rihanna. One aspect of the album which especially appeals to me is the often darker, angrier nature in his delivery on a large handful of tracks, almost suggestive of the album title, “DAMN.”, as being rooted in frustration and distaste with those who surround him in the industry. For newer Kendrick listeners, too, I believe that this is the best album to begin with when taking a delve into his catalog, as it masterfully blends both accessibility on the production and lyrical ends while still being a concept album with diverse storytelling tracks such as FEAR and DUCKWORTH.